The future does not arrive with a bang. It creeps in through side doors: Reddit threads, product update footnotes, the Slack channels where design interns swap Midjourney hacks.

For the better part of a decade, creative software has been ruled by a predictable logic. The more tools you bundle, the more you can charge. Enterprise buyers have been trained to nod along when procurement hands them seven-figure renewals, confident that somewhere, someone is using every license.

That era is over and quietly, a new reality has arrived. Users are no longer assembling workflows from big-box software suites. They are stitching together microtools: lightweight, AI-native utilities optimized for speed and output over brand and legacy. And in doing so, they are rewriting the assumptions that built the empires of Adobe, Salesforce, Microsoft, and others.

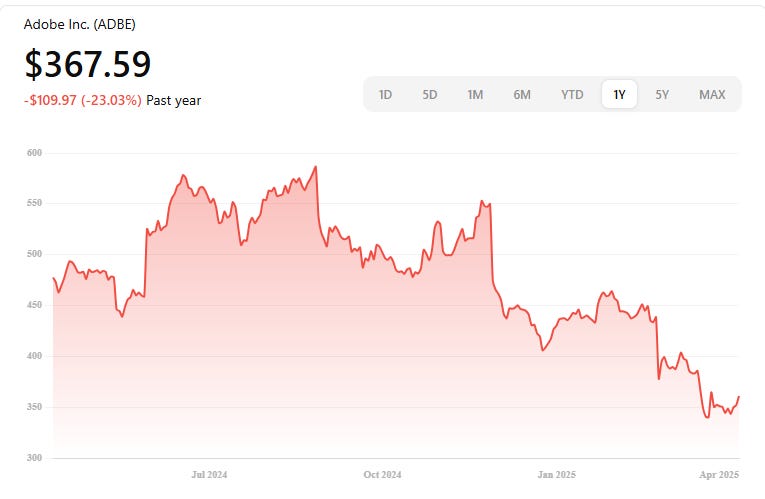

Adobe, still the undisputed heavyweight of the professional creative world, finds itself at the center of this disruption. Its numbers remain impressive. Record revenue. High-margin recurring subscriptions. Billions in ARR. Yet the stock is down sharply over the last year. Analysts are asking why all this Firefly innovation isn’t showing up in the numbers. The concern isn’t that Adobe has lost its technical edge, it’s that the terrain itself has changed.

Generative AI is not eating Photoshop or Premiere Pro head-on. It is eating the tasks that once led people there.

Before we proceed, I’d like to give you a taste of something new⚡ and amazing we’re building:

You’re invited to chat with Dave, my friendly Aussie robot 🤖, about this very article.

Just try giving him a ring at +1-669-322-1626

He’s available 24x7!

Feel free to drop me an email later and let me know how it went.

Midjourney isn’t trying to replace Adobe’s tools. It is replacing the early moments of creative ideation—the messy sketches, moodboards, and reference hunts that used to require hours of manual labor. Runway ML isn’t competing with Premiere feature by feature. It is collapsing video editing, visual effects, and animation into a single promptable interface. Canva, once dismissed as a toy for non-designers, now serves as the default visual engine for over 170 million users. These aren’t head-to-head challengers. They are workflow atomizers.

What’s slipping away from every incumbent is the value of the bundle. For a generation of users who can chain together five browser-based tools for $30 a month and get results in minutes, the argument for paying $659 a year for a suite begins to fray. And in the enterprise, CIOs are starting to question not the tools themselves, but the logic of the seat-based pricing model. Why buy licenses for a team when 80% of the output can be handled by generative agents?

This is not unique to Adobe. Salesforce, the defining software bundle of the customer era, is experiencing its own unraveling. What began as a CRM platform grew into an all-consuming suite of sales, service, marketing, analytics, and automation tools—until it became too bloated to love. Today, revenue operations teams increasingly route around the core CRM, relying instead on AI copilots and lightweight RevOps tools to handle everything from deal scoring to outbound execution. And just as with Adobe, pricing pressure is creeping in. Fewer reps logging into the CRM means fewer seats justified at renewal time. Empires don’t suddenly collapse, they start leaking.

Microsoft, too, is feeling the paradox of scale. Copilot is being heralded as the most important product Microsoft has launched since Azure (as an aside: it is truly, Vista-level awful, and I can’t believe I’m locked into an annual plan). Embedded in Teams, Outlook, Word, and Excel, it’s designed to make Office 365 smarter, faster, and more indispensable. But in the process, Microsoft risks accelerating a future where users don’t care which app they’re in at all. If Copilot drafts the deck, analyzes the spreadsheet, and preps the email thread—does it matter whether it lives in Word or PowerPoint or Excel? Microsoft is simultaneously fortifying its moat and eroding the rationale for its own tools. The brand is still strong. But the user’s point of attachment is shifting from application to agent.

Adobe’s answer has been to integrate AI deeply into its flagship tools. Firefly is not a standalone product; it is an embedded capability, available inside Photoshop, Illustrator, Express, and Premiere. GenStudio promises to unify content creation with marketing activation, building connective tissue across Adobe’s various clouds. These are thoughtful moves. The problem is that they are rooted in a vision where software remains the primary surface of work. Increasingly, that is no longer true.

In a world of agentic AI, the user doesn’t care which app opens. They care that the campaign assets are ready by noon, that the video has been localized into six languages, that the landing page tests are already running. The logic of software-first design—interfaces, menus, layers—is receding. The next generation of creative output will be orchestrated, not manually composed.

Some of this disruption was inevitable. Technology has always lowered the barriers to entry. What makes this moment different is the velocity. In the span of eighteen months, we have gone from “AI can help you write a better caption” to “AI can run your entire design sprint.” The shift from productivity enhancement to capability replacement has been swift and brutal.

What makes this especially challenging for incumbents is that their business models are calibrated for a different set of constraints. Creative Cloud pricing assumes that creation is hard. That tools are powerful. That professionals are willing to pay for control and fidelity. But generative AI doesn’t care about control. It cares about completion. When a model can generate fifty versions of a visual in five seconds, the value doesn’t accrue to the tool—it accrues to the system that knows which version to ship.

This is where Adobe is trying to position itself: as the enterprise’s trusted partner in a world of untrustworthy AI. Firefly’s key differentiator is indemnification. Adobe trains its models on licensed content. It guarantees that enterprise users won’t be sued over a rogue training dataset. It offers brand-specific fine-tuning, governance, and compliance. In a world awash with generative content, Adobe is promising a firewall.

Microsoft, too, is emphasizing trust and governance in its Copilot offering. In enterprise sales cycles, the pitch is not “smarter documents.” It’s safe AI—controlled outputs, corporate data boundaries, and identity-integrated workflows. But as with Adobe, safety is a means of retention, not a growth accelerant. It buys time. It does not create momentum.

Indemnification is a defensive moat, not a growth engine. It appeals to legal teams and risk managers. It does not spark love in professional users. The Suite Empires’ true challenge is cultural. They must convince their user base that what made their tools powerful before—precision, polish, and control—is still worth paying for when “good enough” is one click away.

To win this next chapter, Adobe and its peers must stop talking about features and start talking about outcomes. They must stop thinking like software vendors and start thinking like infrastructure providers for workflow and outcomes. This means leaning into orchestration. It means designing not for use, but for invisibility. The best tools will be the ones no one notices—the ones that sit quietly beneath the agent layer, executing on intent and routing outputs to the right channel.

This also means rethinking pricing from the ground up. The license model is cracking. Credits and consumption tiers are interim solutions. The eventual model will be outcome-aligned: priced on value delivered, not tools accessed. Whether the Suite Empires can make this leap—both operationally and psychologically—remains to be seen.

In many ways, the Suite Empires are well-positioned. They have scale. They have trust. They have embedded workflows inside thousands of the world’s largest organizations. But scale can calcify. Trust can be slow to monetize. And embedded workflows can become legacy liabilities if users begin to defect at the edges.

Salesforce knows this firsthand. The rise of AI-native revenue platforms is prompting startups to rebuild GTM workflows from scratch, and Salesforce's attempts to counter with Genie and EinsteinGPT have not yet delivered a coherent agentic experience. The platform remains dominant, but no longer default. The same pattern is taking shape in the creative stack.

And this is where the work begins—not in the code, but in the clarity. There is an urgent need for companies to map where actual user workflows are breaking, where buyers are quietly seeking alternatives, and where the next round of budget cuts will surface as unmet needs masquerading as feature requests. These are not engineering problems. They are strategic intelligence problems. The winners will be those who understand not just what the customer is doing, but why—and what that behavior reveals about the next phase of value creation.

This is not just Adobe’s problem. It is a warning shot for every B2B SaaS with a suite, every platform built on bundling, every incumbent that believes integration alone is enough to stave off disruption.

The future of creative work will not be built on tools. It will be built on agents, systems, and orchestration layers that deliver outcomes faster, safer, and more intuitively than a human ever could.

The Suite Empires aren’t falling. They are being rearchitected. One user, one workflow, one outcome at a time.

And those who cannot see the difference between a feature and a future will not survive the migration.

Did you try quizzing robot Dave🤖 about this article?

He’s a very knowledgeable and friendly Aussie 🦘 who won’t take offense at anything you throw him.